At just 15 years old, a young innovator, Heman Bekele, has created a breakthrough in skin cancer prevention: a bar of soap designed to fight melanoma and basal cell carcinoma. This unexpected development in the fight against one of the world’s most common cancers shines a light on how youthful ingenuity could reshape the future of public health.

Melanoma is the most dangerous type of skin cancer, primarily caused by increased exposure to UV light. Those who live closer to the equator experience more intense exposure to UV sun rays and are more likely to develop melanoma or basal cell carcinoma.

“For very superficial melanomas, this [soap] could be a solution and possibly preventative [one] to people [who are at higher rates of developing skin cancer]” said Dr. Tina Davis, Upper School Science Department Chair.

According to the American Cancer Society and the American Academy of Dermatology, it is estimated that 200, 340 new melanomas and up to 5.4 million new basal cell carcinomas will be diagnosed in the United States and 10,000 people will die of both diseases in 2024. Currently, the only treatment on the market is surgery, radiation, and chemotherapy— all of which are costly and can impart serious side effects to patients. This new innovation in the treatment of melanoma seeks to provide an alternative to these conventional methods of treatment.

Heman Bekele has set out to create this solution. He was first drawn to this issue when as a child, he watched how the people from his community in Ethiopia would work without sun protection. Desiring equitable distribution of sun protection no matter socio-economic status, Bekele aimed to formulate a cost-effective treatment for early stages of melanoma and Basal cell carcinoma that would be accessible, like a bar of soap. In pursuit of further developing his idea, Heman entered the prestigious 3M Young Scientist Challenge, an annual competition designed to foster innovation in young minds. With the mentorship and guidance of 3M engineers, he refined his design and perfected the formulation of Skin Cancer Treating Soap (SCTS). His hard work and ingenuity paid off when he became the winner of the competition, earning a $25,000 prize, and was awarded the distinction of Time Magazine’s 2024 Kid of the Year.

SCTS takes a new approach by combining a form of imidazoquinoline, a drug proven to effectively treat certain types of skin cancer, called imiquimod, with a lipid-based nanoparticle. This method allows the drug, typically available as a cream, to be integrated into soap. Instead of simply mixing the drug with soap, imiquimod is compounded with a nano-lipid that delivers the imiquimod throughout the skin and remains on the skin after washing the rest of the soap away.

“I do think it’s possible for a product like this to treat skin cancer effectively, especially if we’re talking about basal cell carcinomas,” says Davis. Since topical application of the drug only affects superficial cancers, SCTS is only effective for those who are in very early stages of melanoma or basal cell carcinoma.

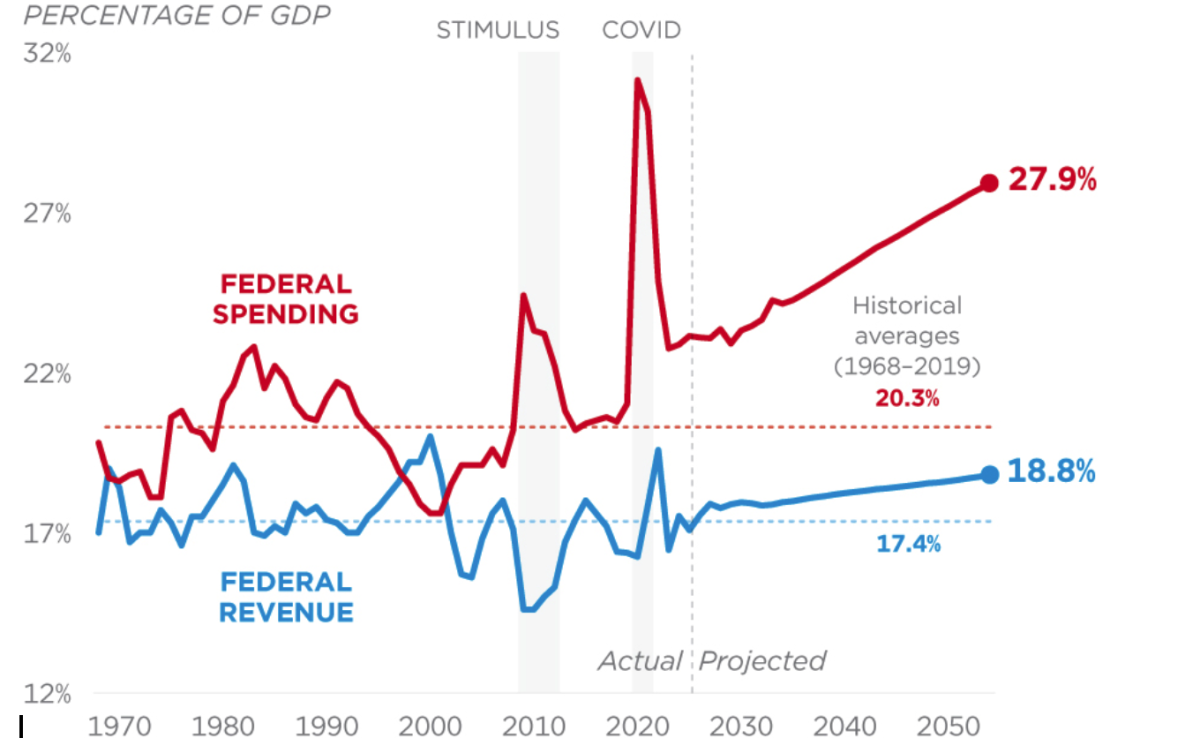

There is a severe financial burden that cancer treatment places on patients. Approximately 25 percent of cancer patients are forced into bankruptcy due to the exorbitant costs, and nearly half (42 percent) end up draining their entire life savings. This directly stems from the extreme economic strain caused by treatments like radiation, chemotherapy, immunotherapy, and surgery, which are often required for cancer care. These treatments are essential for survival but come with overwhelming financial consequences for many patients. The comparison between SCTS and traditional treatment illustrates the stark difference in costs. For instance, from 2016 to 2018, the cost of chemotherapy for melanoma patients averaged around $2,400, which when adjusted for inflation, is roughly $3,000 today. Meanwhile, SCTS, costing just 50 cents to produce, is presented as an incredibly affordable alternative as it is close to 1/5000th of the cost of traditional cancer treatment. This underscores the potential for SCTS to offer a significantly less expensive option for early-stage skin cancer patients. Moreover, the National Cancer Institute’s findings further stress that financial strain can force patients to make difficult decisions, such as skipping treatments or not following through on their medical care, which increases the risk of earlier death. Providing an affordable treatment option like SCTS could alleviate the financial hardships faced by lower-income skin cancer patients and reduce the burden of traditional treatments’ cost and side effects. This could be a potential life-saver for those unable to afford standard therapies.

Right now, SCTS has only been tested in computer-based models and is not FDA certified. However, Bekele has specified that human conducting and getting FDA certified are his goals for the future. Currently, Bekele is focusing on promoting the soap to doctors and scientists, as well as acquiring an FDA certification and a patent for SCTS. The typical process for an FDA certification requires pre-clinical testing (animal testing), an application for the new drug, three phases of clinical trials, and the review and approval process. During the clinical trial step of the FDA approval process, it is essential to ensure that they are conducted with scientific rigor.

“You want trials to be double-blind, with adequate control groups, and controlling [test population] variables,” said Davis.

Typically, it takes around ten years and hundreds of millions of dollars to become FDA approved, so it’s unlikely that SCTS will become available before 2030. However, Bekele is committed to this cause and hopes to found a non-profit organization out of the project by 2028 to benefit as many people as possible. Berkele’s non-profit would focus on ensuring equitable access to the soap, especially in communities that lack affordable healthcare solutions. By collaborating with scientists, doctors, and nongovernmental organizations, Bekele envisions a future where SCTS can be distributed to those in need at minimal or no cost. Additionally, the non-profit would prioritize transparency and research to ensure continuous improvement and adaptation of SCTS, with an emphasis on real-world efficacy once clinical trials are successful.

Edited by Sara Dixon