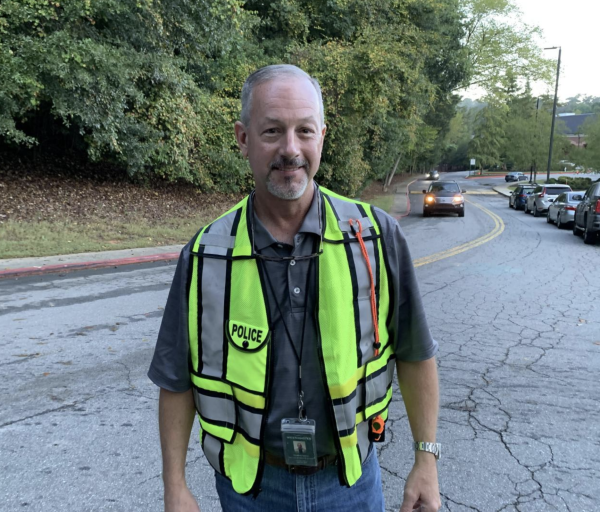

Chauvin trial, Wright death prompt discussion about policing

Last May in Minneapolis, George Floyd died at the hands of police officer Derek Chauvin. The video of Floyd’s death, which showed Chauvin holding his knee on Floyd’s neck as he gasped for air, circulated online, leading to outrage and the summer’s nationwide protests against police brutality.

Chauvin’s trial began on March 29. He was charged with second and third-degree murder and second-degree manslaughter. The main points of contention included whether Chauvin’s actions were within normal policing policy and whether drugs played a role in Floyd’s death. Westminster students and teachers partook in this debate throughout the course of the trial.

“I don’t know a single person who has said that what Chauvin did was justified,” said senior Jonas Du. “No one should be kneeling on someone’s neck for nine minutes.”

Jurors were selected after they completed a 16-page questionnaire asking about their views on issues such as Black Lives Matter and policing. The 12 chosen jurors were more racially diverse than Hennepin County, Minnesota, the county they were chosen from: six were white, four were Black, and two were multiracial (totaling seven women and five men), while Hennepin County is about 74 percent white and 14 percent Black.

During the final days of the trial, police departments across the country prepared for potential protests after the verdict. Two hundred fifty National Guard troops were deployed in Washington, D.C., and Minneapolis public schools shifted to remote learning.

“I was really nervous about the verdict and was thinking the whole day about how it’s going to affect the rest of our lives,” said junior Mykah Boye.

On April 11, twelve days after the trial began, Daunte Wright was fatally shot by a police officer outside of Brooklyn Center, only 10 miles away from the courthouse where Chauvin was on trial, sparking anger and frustration. Demonstrators poured out onto the streets once again, where they clashed with police, shouting “no justice, no peace.”

“[The deaths of Floyd and Wright] sadden and disappoint me, but I’m not really surprised,” said Boye.

Wright was pulled over for a violation related to expired registration tags, but the officers then discovered that he had an outstanding warrant for his arrest. While the officers were attempting to detain Wright, he got back into his car, provoking a struggle between him and the officers. A video from an officer’s body cam then showed one of the officers pointing a gun at Wright, shouting, “Taser!” When the car drove off, the officer shouted an obscenity and said, “I just shot him.” Wright was later found dead from the gunshot wound in his chest. Wright’s death, especially given its proximity to the Chauvin trial, prompted additional discussion and outrage on police use of force.

“The fact that the pretext laws are on the books and that they’re most likely used to pull over people of color rather than whites should give us pause,” said history teacher Ana Maria Szolodko. “Then to hear that the veteran police officer claimed to have confused the two weapons—which don’t feel or look alike at all—seemed even more implausible. This case is deeply disturbing, and I’m afraid just one of many which shows how seemingly innocent traffic stops can quickly escalate into deadly encounters—especially for people of color.”

Du believes that the officer made a mistake, but also believes that it highlights a necessity for reform in police training.

“I’m inclined to believe that it was a genuine error, but a police officer making a mistake is not evidence that the police are systematically flawed and we need to abolish them,” said Du. “It does show, however, a need to improve training to avoid such incidents. We need to better prepare police offers for what they may encounter.”

Boye distinguished between police preventing crime and police responding to crime, saying that we need to “rethink government funding and what police actually do.” Du agreed, citing policies that call for changes in the responsibility of police.

“I think there’s merit to shift some of the responsibilities away from police and toward other social workers in areas that police don’t need to be responding to, such as in instances of mental health, because as we have seen recently, a lot of those incidents have resulted in a use of force that we could have avoided by sending a non-police officer or a social worker,” said Du.

Szolodko believes that “accountability and transparency” is a key place to start with police reform: she pointed to the need for community-based commissions instead of reliance on police to investigate “their own reported violations,” as well as a need for body cameras.

“Transparency means that violent acts — people killed by officers, reported abuse at the hands of officers — should be matters of public record,” Szolodko said. “We should ensure that police officers are trained in serving their community by building relationships within those communities and that the power they hold should be used for service, not control.”

While Du believes that the push for police reform is a positive and important change, he called the “negative perception of police in the past year largely detrimental to society.” He said that the police need to be people we can trust.

“Seeing the police as an evil force in society out to get minority communities is very counterproductive,” Du said. “Police are responding to crimes, which disproportionately hit such communities, so when you have viral incidents of police brutality and you have a prevailing narrative about racism and police, you’re really going to be harming those communities.”

Boye disagreed, believing that a negative view of police is crucial to changing the “system.”

“ I think that it is a necessary step because for change to happen, you have to recognize that there’s a problem, and I think right now, people are in the recognition stage,” Boye said. “The negative perception of police can push organizations to change how they operate, which is what is going to make change actually happen—as opposed to just hating each other, we need to use it as a movement for change.”

On April 20, Derek Chauvin was convicted on all three charges in the killing of George Floyd, facing up to 40 years in prison for second-degree murder, up to 25 years for third-degree murder, and up to 10 years for second-degree manslaughter.

Boye and Szolodko both expressed relief at the verdict.

“I’m relieved,” said Boye. “It feels like a weight’s been lifted off my shoulders, and it makes me feel like we’re achieving something.”

“My initial reaction to the verdict was a profound exhale—I think it was relief and certainly not rejoicing,” said Szolodko. “I believe that it is a step in the right direction, and I think that people will feel that this is an acknowledgment that policing in America needs reform and that bad policemen can’t act with impunity. … It means that we know we as citizens can act—even in small ways—to root out injustice when we see it.”