Kavanaugh confirmation process calls into question issues of sexual assault and political division

On Oct. 6, a 50-48 vote in the Senate confirmed Justice Brett Kavanaugh to the US Supreme Court, ending one of the most turbulent confirmation processes in American history. Amid the calls of Democratic senators to adjourn due to insufficient time to review the judge’s documents, Senate Judiciary Chairman Chuck Grassley proceeded with the initial hearings that lasted from Sept. 4-7. On the first day alone, police arrested 70 protesters interrupting the hearings. Nevertheless, other voices only continued to overlap the confirmation process. Over a week later, Dr. Christine Blasey Ford revealed her identity as the writer of an anonymous account in the New York Times that claimed Kavanaugh had, under the influence of alcohol, sexually assaulted her while they attended high school. Before her public account in the New York Times, Ford had already informed Senator Dianne Feinstein of the alleged incident in a letter in July, after Trump had announced his choice to nominate Kavanaugh. Ford had wished to keep it private in order to protect her identity. Tensions boiled to their height as the Senate Judiciary Committee met once again on Sept. 27 and 28 to hear the testimonies of both parties.

On the cusp of the “Me Too” movement, Ford’s allegations against Justice Kavanaugh have added to the growing body of sexual assault accusations against individuals in high-profile positions. For some, however, the little evidence and witnesses corroborating certain cases calls into question their validity.

“The Me Too movement is doing a great job of bringing women together, but I think in this case it’s beyond believing women and it’s just believing the truth,” said senior Lizzie Portwood.

To spectators of all political leanings, though, the truth of this particular case seemed more elusive. In their opening statements and the subsequent questioning period, Kavanaugh and Ford provided contradicting details surrounding the incident – the country club gathering where it allegedly occurred, the people present, and the degree of acquaintance between the two. Requested by Senator Jeff Flake after the hearings, the supplementary FBI investigation into the allegation provided what many believed to be inconclusive evidence. Out of the nine witnesses interviewed, classmates of Ford and Kavanaugh in high school and college, three, including Ford’s high school friend Leland Keyser, claimed to not remember the gathering that happened over thirty-six years ago, denied seeing Kavanaugh there, or denied his role in the assault.

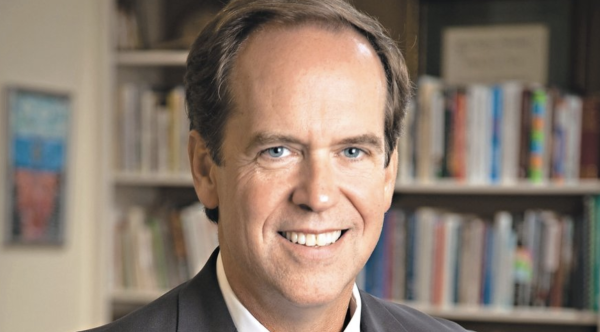

“Beyond the human drama of it all, for someone who deeply believes in our democratic republic, it was a disappointing exercise because even with the FBI’s follow-up investigation, I don’t think anyone feels satisfied that we know the whole story,” said AP US History teacher John Monahan.

According to Dr. Dena Scott, a clinical psychologist at Westminster, discrepancies in memory often occur as a result of trauma. When victims must recall past experiences, even those from decades ago, they risk re-traumatization. “I think it’s hard when we see somebody and they’re sharing their story, and we’re finding holes and difficulties in how we’re receiving it,” said Scott. “And not to say that we’re not supposed to be trying to look deeper, but I think that we have to look at the facts of when you’re talking about trauma, and especially something that has really impacted you in a large way… We have to be aware of that, because otherwise we’re setting ourselves up in finding everybody’s stories flawed and problematic.”

Accusations of this level, if proven true, could result in a loss of job and credibility for the accused. The lack of decisive evidence has led some to take the ‘innocent until proven guilty’ approach; namely, to grant Kavanaugh the benefit of the doubt.

“Everyone acknowledged the man’s fairness, his objectivity,” said US History teacher Joe Tribble. “He was kind of the ideal judge in everyone’s mind. And to see someone like that who puts everything on the line, his life, his reputation, his family, to see someone like that attacked with absolutely no basis… he was vindicated.”

To others, Kavanaugh’s apparent political leanings calls into question his ability to serve on the Supreme Court without the influence of partisan politics or personal interests. In his opening statement, Kavanaugh characterized the accusations, the questioning process, and the media coverage of the hearings as a “calculated and orchestrated political hit, fueled with apparent pent-up anger about President Trump and the 2016 election.”

“It’s hard to say that he was justified if we’re talking about someone who’s now going to go forward and claim to be impartial, and now has set this precedent where emotional manipulation to get an outcome can succeed as part of a confirmation process,” said Monahan. “On some level, don’t nominees have a duty to consider the impact on their own nomination, but also on all nominations?”

Nevertheless, some, like senior Edward Shores, believe that the media backlash Kavanaugh faced accounted for his spirited deportment during the proceedings. The personal circumstances surrounding the hearings, said Shores, posed an exception and did not depict his conduct in court.

“I think Dr. Ford didn’t intend for it to be that way, but the Democrats… were very aggressive in their lines of questioning to Mr. Kavanaugh, like asking him about his high school yearbook, references to alcohol or girls, that should not be brought up before a Supreme Court nominee, because he’s forty years removed from that,” said Shores. “That would be like someone taking a quote from me yesterday and bringing it up in court forty years from now, saying that I’m the same person.”

On the other hand, the negative media attention against those who have come forward with sexual assault claims also reduces the plausibility of their being used as a political tactic, according to Gender Equality and Relations club president junior Payton Selby and senior Saige Haynes, the leader of BRIDGE.

“It never really benefits the victim to come out,” said Haynes. “And I think what proves that is that it takes so long for the victim to speak out and oftentimes, they want to stay anonymous, and they’re just coming because they know how horrible it will be for someone who has sexually assaulted another human being to hold such a powerful position.”

Ford, in her opening statement, emphasized that she did not seek to legally prosecute for ulterior motives. “I am here today not because I want to be,” Ford said. “I am terrified. I am here because I believe it is my civic duty to tell you what happened to me while Brett Kavanaugh and I were in high school.”

Moreover, the nature of Ford’s accusation may prevent Kavanaugh, if found guilty, from facing legal consequences. Maryland, where the alleged incident occurred, has no statute of limitations for attempted rape which restricts the amount of time from a crime in which accusers may take legal action. Ford’s accusation, however, would have been classified as a “misdemeanor” in 1982, and criminal cases follow the laws of the time of which they were committed. In other words, said Monahan, the confirmation process was not a criminal trial, and applying the ‘innocent until proven guilty’ approach would be inappropriate.

What’s more, said Selby, Kavanaugh’s confirmation itself sent an ominous message for current and future civil rights cases examined by the Supreme Court. Before the Senate Judiciary Committee, however, Kavanaugh stated that one of his friends, a survivor of sexual abuse, had confided to him in 1990. “Allegations of sexual assault must always be taken seriously, always,” said Kavanaugh in his opening address. “Those who make allegations always deserve to be heard.”

Although many have pointed to positive testimonies of Kavanaugh’s personal character as evidence for innocence, according to Selby, any possibility of appointing a perpetrator of sexual assault to the Supreme Court far outweighs the consequences of denying Justice Kavanaugh his position.

“When we look into it, we really have to look at the court and their ability to excuse sexual assault allegations as not that big of a deal unless it can be proven, [which] kind of speaks to the legitimacy they give women and their voices and their stories,” said Selby. “I think at the end of the day, the decision that should have been made was that if there is an allegation against him, and he couldn’t be proven innocent just as much as he could be proven guilty, that it really comes down to how seriously are we going to take issues of sexual assault that plague women.”

Beyond this particular case, though, said Scott, cultivating a meaningful solution requires a step back from the individual players–Kavanaugh and Ford–in order to examine the overarching societal forces at work. Scott has worked with children identified as perpetrators of sexual harassment; her perspective, she said, has given her insight on the impact of the roles assigned to individuals.

“Not to say that if somebody has engaged in something that is inappropriate… that there shouldn’t be some level of support or some process of healing for the person that was on the other side, but I think also sometimes, how we are as a culture in terms of wanting to just label and identify a ‘bad’ doesn’t always get to the end result of trying to support there being a change in our culture, a change in our system,” said Scott.

In terms of the Supreme Court, said Monahan, the road to nomination and confirmation should more deliberately account for the voices of individuals and their state representatives earlier in the process. “Behind the scenes are these massive concentrations of political partisans and of money to influence who ends up on the stage, which is the only stage where most of us have the time to start paying attention,” said Monahan. “And by that time, in some ways, it’s too late in the process to say, ‘I don’t exactly like this guy, can we find someone more moderate?’”

Regarding societal structures, said Scott, intentional conversation behind the way our society views sex, sexuality, and power dynamics are necessary to process the recent events. Just as the hearing revealed deep divides in the Senate, the debate surrounding the confirmation and sexual assault triggered a polarized student response. From hearing snippets of opinions around campus, Haynes decided to initiate a discussion in BRIDGE surrounding sexual assault on Oct. 5. The Westminster community, she knew, needed an open discussion. On Oct. 5, however, Haynes did not anticipate that students would crowd around the doors, sit on the floor, and overflow from the room. Still, many people showed up for the “drama,” jeopardizing the club’s role as a safe space, according to Haynes. In addition, she believed that some parts of the discussion exhibited an inability to listen to a different perspective, the same attitude that seemed to characterize the Kavanaugh proceedings.

“It’s frustrating when people enter discussion with the single intent to discredit someone else’s facts or information, rather than entering a discussion wanting to learn,” said Haynes. “I think that was what was happening in the BRIDGE discussion. Some people came in there and had their computers open and were just trying to fact-check everybody, trying to discredit what they were saying.”

Similarly, said Shores, others in the room did not allow him the chance to express his position. For instance, Shores believed that his point about the existence of rape culture was misinterpreted.

“I said the thing about my statistic and I got interrupted by eight girls, and then the same thing happened to Will Wallace,” said Shores. “It’s not like me saying that rape culture doesn’t exist in America is me saying that I don’t like women, it’s me saying that I don’t think rape is okay anywhere in the country.”

Despite a few exceptions, many students in the room sensed a divide between the viewpoints expressed by different genders. Both Shores and Haynes agreed the way most boys and girls sat on opposite sides of the room further heightened the tension and contributed to the “battleground” mentality. Though the victims of sexual crimes and its perpetrators can be of any gender, said Haynes, the hypersexualization of women contributes to the attitude that degrades and takes the power of consent away from women. According to those present at the discussion, disagreements over the definition of the “rape culture” mentioned by Shores was a main point of contention.

“[Rape culture] just means that we live in a society where it’s extremely normalized, and sexual harassment is something that girls have to learn to deal with and react to since they’re prepubescent, like their moms are telling them ‘Don’t put your drink down’ and how you have these unspoken codes,” said Haynes. “Women are not the only victims of sexual assault; men are as well, but the majority of them are women, and it’s frustrating when you see boys in your community, not listening to you, a female, who is living this life, living through this culture, and not at least wanting to hear your perspective out.”

In Shores’ perspective, however, girls were able to express their opinions as much as, if not more than the boys. This gender divide, said Scott, stemmed from our society’s unspoken association of the role of a perpetrator with males; though all males are not perpetrators, we tend to believe that those who sexual harass somebody are usually male, said Scott. According to her, the difficulty lies in bringing in a variety of opinions without positioning viewpoints as personal attacks to another’s experience.

“Unconsciously, there may be a sense of, ‘I don’t want to be seen as a possible rapist,’” said Scott. “’As a male, if that all goes away and there is no rape culture, then I will not be seen in that role, because that role is painful and that role is problematic, and that role comes with a lot of complex, challenging things that many people don’t want to be associated with,’ but it doesn’t mean that rape culture doesn’t exist.”

On the other hand, some girls like Portwood believed that, although necessary, a full shift in culture and the eradication of sexual crimes is easier said than done. As unfair as it seems, said Portwood, for now, women should be careful.

“I think consent in a lot of guys’ eyes, horrible as it may be, is when girls put themselves in vulnerable situations, like wearing clothes… or being intoxicated,” said Portwood. “Unless our society’s changed, almost in their hearts, I don’t think it’s going to change anytime soon, and I don’t think people support it but it definitely happens, and I don’t have a solution at all.”

As a first step, said Scott, dialogue surrounding boundaries and consent becomes imperative to address in high school. According to Scott, the administration is working to cultivate a healthier environment for that dialogue. In addition, through awareness campaigns and an ongoing partnership with the Wellspring Living shelter for victims of sex trafficking and sexual abuse, GEAR has directed its focus to sexual harassment on campus. This year, the club plans to educate students about laws surrounding consent, pictures, age, and the common behaviors that may constitute a felony.

Furthermore, said Portwood, despite the tense environment, those involved in the BRIDGE discussion still shared a common goal of determining a solution. Likewise, as many hoped, the senators present at the Kavanaugh confirmation hearings all sought, ideally, to determine the best possible justice for the country. As many believe, however, the problem arises when we lose sight of the goal.

If you or someone you know is or has been the victim of sexual assault or harassment, please reach out to one of the counsellors at the Wellness Center.