Atlantans’ fear of Ebola demonstrates confusion, ignorance

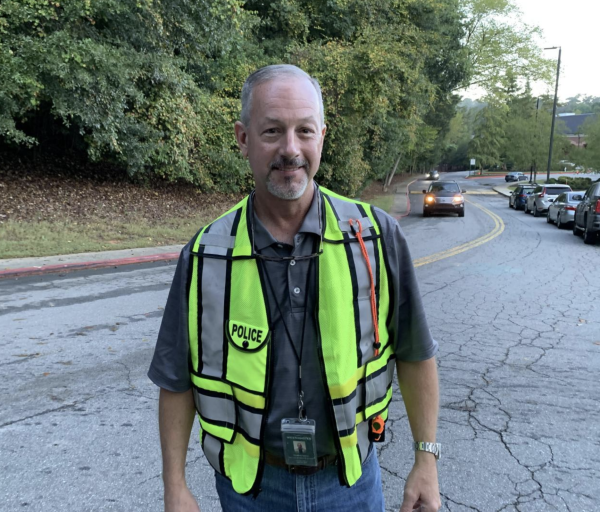

On Aug. 21, Dr. Kent Brantley was released from Emory University Hospital after his labs tested negative for the Ebola virus, the virus responsible for taking over 2000 lives in West Africa over the past six months.

Brantley and Nancy Writebol are the only two individuals who are known to have crossed into the United States while carrying the Ebola virus. They were both treated at Emory University Hospital, less than nine miles away from Westminster’s campus. Despite the school’s close proximity to a hospital with such recent international attention, some students aren’t familiar with the Ebola virus and its recent outbreak in West Africa.

In the Westminster community, an apocalyptic, Contagion-starring-Gwyneth-Paltrow-like stigma surrounds the Ebola virus. The arrival of the infected patients to their hometown scared many students.

“I think I’m scared, cause your first thought is ‘Wait, could it spread over here?’” said junior Amanda Brothers. “I’m scared about getting it, because the symptoms aren’t immediate and just so many people come here and Ebola could come here and spread here. That would be so scary.”

Freshman Miller Polly shares Brothers’ fear of an Ebola outbreak in Atlanta, saying he was afraid for himself and his community.

“I was super scared! Because they have a chance of dying,” Polly said. “And I didn’t know if any of my friends or family were going to get it, so yeah, I was scared.”

This sort of perspective needs to be reframed, explains Dr. Kimberley Workowski, an infectious disease professor at the Emory School of Medicine. It’s more important to think of the outbreak on a global perspective rather than a “Buckhead bubble” perspective, Workowski says.

“At Westminster you’re hearing ‘I’m scared for me’ or ‘I’m scared for my family,’ which is not the humanitarian perspective—it’s me-mentality,” said Workowski. “As researchers, we have to think about how we can help global health and contain this epidemic, not how can I help myself.”

Students don’t need to be scared of contracting Ebola from the patients at Emory, because Emory and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, or CDC, are well equipped to control and contain the infection. Originally built in case CDC workers got sick while working in the field, a special infectious-diseases unit funded by the CDC is used especially for treating patients with viral infections.

“Emory built a separate, self-contained isolation unit funded by the CDC with specially trained staff to deal and contain these types of diseases,” said Workowski. “Emory is contracted to take care of CDC workers if they get sick while in the field. The isolation unit is one of only four in the country that can deal with infected people in such an isolated way.”

Dr. Kasia Kaufman, teacher of AP Biology and the Plagues: The Science, History, and Mathematics of Disease Jan-Term class at Westminster, explained the isolated way in which the Ebola patients were treated. All of the bed linens, clothing, and anything that came into contact with the infected patients were autoclaved.

“You can think of an autoclave as a really big pressure cooker,” said Kaufman. “It heats things up really really hot, under high pressure, and it sterilizes them. So anything that comes out of an autoclave is sterile.”

After being autoclaved, the patients’ waste is disposed in a special way that is unique to medical waste, even though it’s technically already sanitary.

“And they still take extra precautions—they still treated everything as medical waste and threw them away, after it was autoclaved,” Kaufman said. “But throwing it away in a special way that is reserved for medical waste.”

And although the Ebola virus is not airborne, the air in Emory’s isolation unit is filtered and treated after coming into contact with the patients. The unit exists to make sure that any type of disease, including Ebola, cannot get out.

“[The isolation unit] has laminar air flow so that the air comes in through the ceiling and goes out through the floor, so that the air cannot leave the room, in a way,” said Kaufman. “The air flow prevents any sort of air from even leaving that room without being filtered.”

Despite all of these precautions and Emory’s and the CDC’s evident ability to contain the Ebola virus, junior Harrison Gould was still unhappy with the arrival of the Ebola patients in Atlanta.

“I was frightened. I was extremely frightened. I thought I might get it,” said Gould. “When they left, I was very relieved.”

Laura Schramn, junior, while not as scared as Gould, still felt that the Ebola patients’ presence affected her lifestyle in Atlanta. Schramn says that she trusted the doctors to take contain the virus but still wouldn’t visit Emory while the patients were there, just to be safe.

“I wasn’t scared because I knew that the doctors probably knew how to handle the patients and everything, but I wasn’t about to go to Emory for any reason,” said Shramn. “While the Ebola patients were there, I would definitely not go for a check-up at Emory or swim in the Emory pool.”

Doctors Kaufman and Workowski agree that more education surrounding the virus is needed to ease student anxiety and change these types of opinions.

“Having Ebola patients at Emory really doesn’t affect the Westminster students,” said Workowski. “This brings up the importance of being educated about the virus.”

This misinformed fear regarding Ebola is not unique to the Westminster community, adds Kaufman. With more education on the science of the virus, people won’t feel as scared.

“I think a lot of people are scared, not necessarily just at Westminster. I know just on my Facebook feed, I had a lot of people that were expressing their dissatisfaction with the fact that Emory, just a few miles away, had Ebola patients,” said Kaufman. “But I think that with some more knowledge about the disease, your fears can be put to rest.”

Workowski thinks that the fear comes from Ebola’s climbing death toll, which actually results from West Africa’s generally unsanitary hospital conditions rather than the disease itself. And unlike other epidemics, Ebola can only be spread through prolonged contact with infected bodily fluid, making it more difficult to contract than diseases such as tuberculosis.

“People are nervous because of the high mortality rate, but they don’t know anything about how the virus is spread,” Workowski said. “It’s difficult to get Ebola. People don’t understand that it’s not airborne—you can’t just walk by someone and get Ebola.”

“Ebola can only be contracted by direct contact with infected bodily fluids,” adds Kaufman. “So as long as you don’t do that, you’ll be okay. So as far as the patients being at Emory, there’s not really a chance of Ebola spreading to the Atlanta area.”

Ebola is taking so many lives in West Africa because of the unsanitary conditions and lack of medical supplies. A large part of why Brantley and Writebol experienced such a successful recovery from Ebola is due in part to what many students at Westminster take for granted.

“We’re not sure if the strain of Ebola that the patients at Emory had was the same strain that has such a high mortality rate in West Africa. The patients might have had a different existing strain of Ebola and simply got better on their own,” Workowski said. “People here take for granted what Emory facilities have—trained doctors, sanitary conditions, means of hydrating and getting the patients nutrients. Meanwhile, some West African hospitals have to reuse needles.”

With the correct decontamination procedures, it’s relatively easy to control and contain the Ebola virus.

“I know there’s a lot of fear about Ebola now, like people are worrying that it’s going to spread,” said Kaufman. “But it’s really pretty easy to contain, if you just take proper sanitation measures and proper decontamination measures. But in West Africa they don’t always have those things and they don’t always follow the proper protocols.”

Dr. Amy Chen, an Emory otolaryngology surgeon who spent time doing volunteer surgery in Nairobi, has experienced these hospital environments firsthand.

“There’s not a lot of sterile technique—the basic precautions such as wearing gloves and a mask that would prevent the spread of communicable diseases is just not present or feasible in most of Africa,” Chen said. “There is a lack of supplies and a lack of infrastructure.”

While some students are fearful of the disease, freshman Anna Wilkinson has a different perspective.

“I was not scared at all,” said Wilkinson. “I don’t even really care that much. It’s a part of life. Some infected people have to go to different places. Whatever. We’re not going to die.”

Students like senior Aaron Shaw and freshman Alex Pirouz are not scared either—instead, they are happy that the patients received the medical treatment that they needed.

“Chances are, we’re not going to get it,” said Pirouz. “So I wish that they get better, and that we don’t get it.”

“I’m glad that they were here, getting saved,” said Shaw.

Students with more education about the disease generally seemed less anxious about it spreading throughout Atlanta. Junior Anna Lemaster said she was not scared of being infected by the patients at Emory, because she had done extensive research on the virus throughout the summer.

“When I first heard about people coming to be treated in Atlanta, I didn’t know what Ebola was, so I looked it up,” said Lemaster. “I ended up doing my summer reading on the epidemiology of Ebola. I wasn’t scared that I would get it.”

Freshman Mason Wright said he followed the media’s reports on Ebola closely and wasn’t scared either.

“I wasn’t scared that I was going to get sick,” Wright said. “I knew that they had it under control.”

Sophomore Owen Ladner attends Glenn Memorial United Methodist Church, the closest church in Atlanta to the Ebola patients’ isolation unit (the church is less than a mile away). He says he is proud of his church and of Emory for having the capacity to contain the virus and cure the patients.

“I wasn’t scared, because they put the Ebola patients at Emory, so obviously Emory is good,” Ladner said. “I was really proud of Emory and the CDC.”